Brookline Jazz Age Driving

To drive an automobile in the 1920s was to operate a potentially deadly machine in an environment designed for the horse & buggy. During the decade, the number of cars on the road would jump from six million in 1920 to more than 20 million by 1930, and yet, the entire automobile experience remained in its infancy. At most major intersections, a lone traffic cop attempted to direct the chaos of pedestrians, horses, and crisscrossing automobiles all competing for the right-of-way. The interior of the car itself was a dangerous collection of protruding nobs, seats without seatbelts, and glass that shattered upon impact. Driving laws were often ignored and the licensing system was just getting started. In Brookline, the Chronicle became a catalogue of traffic accidents and fatalities on the inside news pages while the editorial staff spent much of the decade suggesting traffic and driving improvements for the town. In short, 1920s Brookline was the driving equivalent of the wild, wild west.

Brookline Chronicle readers could often read about traffic fatalities but the August 29, 1929 edition actually reported two deadly crashes in town — one of which took the life of a 5-year-old boy. On August 22nd, a truck driven by a Somerville man ran over Tommy Mullen of Cameron Street as the boy was crossing Boylston near Cyrpress. According to the paper, the “front left wheel of the truck passed over his body” and he was rushed to Children’s Hospital in Boston, dead on arrival. Three days later, on Harvard Street near St. Mary’s, 27-year-old Charles Sherer of Dorchester swerved his truck onto the street grade tracks of the Boston Elevated and crashed head-on into a two-car train on the Allston-Dudley line. Sherer was thrown from the truck and sustained a fractured skull, dying the same evening at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital.

Other collisions were not fatal but caused plenty of damage — sometimes to reputation. One such accident in August 1928 involved Miss Russella Andrews, a teenager living on Parkman Street. Traveling at an excessive speed down Washington Street, she barreled into motorcycle police officer James McCracken near Park Street, resulting in the eventual amputation of the officer's right leg. The newspaper inaccurately reported the driver to be the daughter of Governor Council member Esther Andrews and apparently some political hay was made of the relation until Mrs. Andrews wrote in to complain that the younger Miss Andrews was not, in fact, her daughter.

Poor driving was certainly to blame in many of the era’s smash-ups. For instance, Boston banker Alexander Campbell of Walnut Street was driving erratically in May 1925 when he ran into another automobile near Coolidge Corner and went careening into a streetcar. His two passengers, Joseph Heath and David Whittier, were killed instantly. The incident highlights the lax penalties still associated with driving automobiles in the mid-20s. Despite being convicted by a jury for driving so as to “endanger the lives and safety of the public,” Alexander received just a $200 fine and a two-week jail sentence. While Massachusetts did begin handing out licenses in 1920, many drivers did not pay much heed to the notion that government approval was needed to operate a purchased automobile.

Road conditions and poorly designed cars were also factors in many crashes. In a 1928 “Note and Comment,” the Chronicle cautioned against speeding “downgrade” on rainy days on Washington Street. “Much property damage has been caused by skidding machines,” the paper noted. “When drivers get the hand signal from the traffic officer at Kent Street, the trouble begins. They try to pull up their cars and fail miserably, owing to the slimy conditions. If the cars don’t skid into other machines, they crash against poles or anything else that happens to be in the path.” Such cars were operating with tires that today would be considered bald, and skidding was common. In October of 1927, the paper warned that “the leaves are beginning to fall and when they come in contact with wet pavement, the combination is an exceedingly dangerous one. It is well-nigh impossible to prevent skidding under such conditions and that’s why so many accidents occur in October.”

Throughout the 1920s, towns across the nation were beginning the process of installing electric traffic lights at busy intersections. In August 1928, the Chronicle mentioned one such hot spot, the corner of Kent Street and Aspinwall Avenue, the sight of “numerous automobile accidents.” Unfortunately, after the board of selectmen voted for a traffic light installation at the corner, the town still had to wait four months for their arrival. Meanwhile, another crash occurred “shortly before the light arrived,” leading to internal injuries for a Brighton man.

The behavior of pedestrians was apparently also a concern. In the days before crosswalks and an orderly street grid, pedestrians were just another one of the many forms of competing transportation. The Chronicle called for jaywalking laws in 1920 while critiquing pedestrians for “disregarding the warning signal of the traffic officer; choosing the most convenient point of crossing and exercising less care than if they were crossing a pasture.” The editorial went on to lecture that the middle of Brookline's Harvard Square is not the place for “one woman to stop another and inquire after baby’s latest tooth, nor for one man to stop another to discuss Harding and Cox, or the latest statement of Ponzi.”

By the end of the decade, the town had acquired more traffic lights, laid crosswalks down at some intersections, and generally improved street patterns. However, it would be many decades before Brookliners would enjoy anything that a modern driver would consider “safe” – if indeed that word can ever be applied to the practice of driving two-ton machines at a high rate of speed.

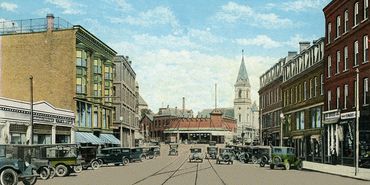

Above Left: 1920s-era automobiles in Brookline Village. (Brookline Historical Society)

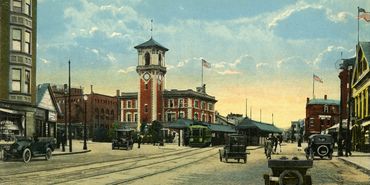

Above Right: Looking west on Boylston Street in the 1920s. (Brookline Historical Society)