Brookline Ramps Up

There are not too many folks around anymore who remember what it is like when the United States mobilizes for a popular war. There was certainly a unity of spirit in America following the 9/11 terrorist attacks but none of the U.S. wars in the Middle East — or certainly Vietnam — had either the widespread popularity or the need for full-scale mobilization as the two great wars of the first half of the 20th century. During the spring of 1917, for instance, an entire nation bent its efforts towards the single purpose of revving up what would later be called the “Arsenal of Democracy,” as the nation prepared to join the WW I fight. Looking back at those frenetic early days of April, May, and June here in Brookline, one sees the entire citizenry of one town moving en masse in this mission.

Congress voted to declare war on Germany on April 6, 1917, following President Woodrow Wilson’s request for "a war to end all wars." Just eight days later, more than fifteen hundred Brookliners gathered in Town Hall for a raucous rally sponsored by the Brookline Public Safety Committee. The Brookline Chronicle described the scene: “Patriotism pulsated with a biff-bang-boom-bang, the flutter of over a thousand flags and bursts of thrilling oratory. The building reverberated with national airs, played by the Harvard Band and sung by a chorus of over 1500 voices, all waving the Stars & Stripes in rhythm with ‘America,’ ‘Tipperary,’ ‘Columbia,’ and ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’”

Throughout April and May, town authorities were in a flurry of motivating zeal to make sure all local men registered for the war. To not do so was to risk becoming a town pariah — as evidenced by a front-page article from the Chronicle entitled “No Excuse for Slackers.” The paper warned, “It remains only for these young men to fulfill their obligations to their country and to themselves. Not to do this will be an unpardonable offense against the government and against their own manhood.” On Tuesday, June 13, some 2,194 Brookline men between the ages of 21 and 31 paid heed, lining up at Beacon Hall and enrolling for service. Afterwards, the Chronicle boasted: “There was not a hitch in the proceedings, not a single instance of unpleasantness.” But just in case, the Brookline Townsman reported on July 7 that “Brookline Police are rounding up draft dodgers,” even if — as the article went on to say — no arrests had yet been made. Nevertheless, it seemed the Brookline newspapers were going to make absolutely sure that every local man did his duty.

Most women also played a role in the war effort, a large percentage of them working in the Red Cross. During World War I, there were 4,418 Brookline Red Cross members and the town raised more than $100,000 for the organization. If anyone had any trouble deciding how to help during the war, the front page of the Chronicle of April 21 was ready to lend a hand. Underneath the headline “Pick Your ‘Bit’ from the List Below and Then ‘Do’ It,” the paper listed various ways that any citizen could assist in the war effort, helpfully sectioning off the duties into categories for men, women, and children. Ladies could find a column entitled “If you are a WOMAN, you can work” with listed options such as the Red Cross, Special Aide Society and so on, with details on how to contact each group.

Other articles attest to the degree to which local merchants participated in the war effort. A group of Brookline dentists, for instance, offered services “to those men who may be prevented from entering the Army or Navy on the condition of their teeth” — which may have reminded some of the old question among dental rejects to serve: “Are we planning to bite the enemy to death?”

“Poorer women,” according to the Chronicle were also “anxious to do their share of the work” and having taken up a discounted rate of ten cents to join the Special Aid Society, many helped decorate Town Hall in patriotic banners and colors. At the Pierce School, the boys of 1917 emulated the class of 1861 after a flag once proudly carried by the Civil War boys at the head of their company was rescued from the dusty eaves of the school attic. Meanwhile, local Girl Scouts were trained to be used in a war messenger service.

The Chronicle also reported that the library was “alive with the issues of the day, constantly buying in military and naval matters,” and then added a bit parochially, “Brookline people may save many visits to Boston libraries if they will but consult the published book lists of their own town library.” Indeed, the months of April, May, and June of 1917 featured war-related articles on such varied topics as emergency phone calls, safeguarding valuables, home gardening, and even the preserving and canning of vegetables.

Indeed, the full impact of the ramp up seemed so all-encompassing that the Chronicle of May 19 seemed to beg for a respite, even if it was from itself: “Seven days of the week, newspapers are filled with war news and comment, and conversation inevitably veers around to the same subject,” the paper grumbled. But there was no letting up. The fighting would rage “over there” while the efforts on the Homefront would continue at full speed “over here,” until Armistice Day on November 11, 1918.

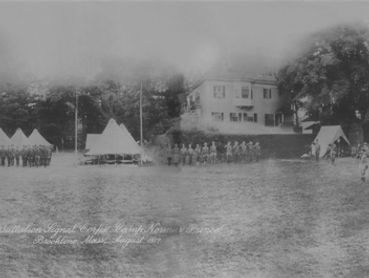

Above Left: The 101st Field Signal Battalion Corps set up in camp near Dummer Street in 1917. (Brookline Historical Society)

Above Right: Town Hall was filled with more than 1500 people cheering the war effort in April 1917. (Brookline Historical Society)