From Weld to Larz Anderson

Some warm spring day fill up your picnic basket, get out your kite, and head to Larz Anderson Park — it’s one of Brookline’s true gems. There’s likely to be plenty of kids on the playground, a ballgame in progress, and a few frisbees being tossed around. Indeed, Larz Anderson Park is a success story of how a once provincial estate for the super-rich became a public park for everybody. But the journey wasn’t easy, and a great deal was lost along the way.

When Isabel Weld Anderson, socialite heiress of $14 million and widow of ambassador and diplomat Larz Anderson, died in November 1948, she unexpectedly bequeathed her 65-acre estate to the town of Brookline on condition that it be used for “educational, charitable, or recreational purposes.” Everyone could see that Brookline was getting one potentially fantastic park free of charge, but the gift also raised what the Chronicle called a “perplexing problem” for the town.

The estate called Weld had been purchased by the Andersons from one of Isabel’s wealthy cousins in 1899, and despite living in Washington for much of the year, it quickly became their playground. The couple was well-traveled. Larz served as ambassador to Japan and held diplomatic posts in Italy, Belgium, and points beyond, and the Andersons spared no expense in bringing their global tastes to Brookline. Hiring the top landscape architects of the day, Weld soon featured an Italian garden, a Chinese pagoda, a Japanese garden, and various dwellings, footbridges, and carvings rendered in a mix of international styles. The result was “something new, something American,” according to landscape historian Robin Karson.

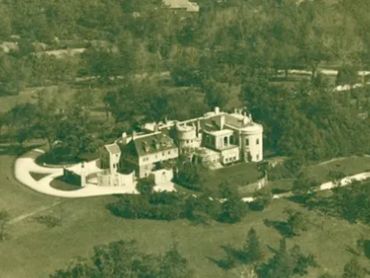

At the very top of Weld Hill stood a rambling 25-room manor house designed to replicate England’s Castle Lulworth. In addition, the accompanying carriage house was not exactly a backyard garage. This immense building hosted a truly rich man’s hobby — car collecting. Long before Ralph Lauren or Jay Leno began buying up automobiles like so many Matchbox toys, Larz Anderson assembled one of the world’s great collections, totaling more than fifty cars dating back to 1898. When the ambassador died in 1937, Henry Ford tried to buy the collection for a million bucks, but Isabel turned him down flat.

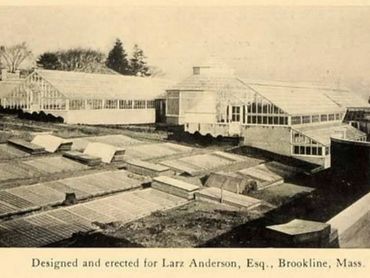

The Weld estate also included stables, multiple greenhouses, a “Temple of Love,” an outdoor theater, a bowling green — and in true well-to-do European style — a polo grounds. By the middle of the century, the rolling hills and tucked-away gardens had become a reminder of the rural retreat that Brookline once was.

Yet many town officials were taking a hard look at this gift horse in the mouth. The Brookline Taxpayer’s Association, for one, essentially said thanks but no thanks to Mrs. Anderson’s generosity. To accept the bequest, “The town would be faced with a continual barrage of requests for large capital expenditures,” said the group’s president. Meanwhile, a study group created to make recommendations to the upcoming Town Meeting voted 4-3 to reject the gift, saying Brookline should have a “restriction of enthusiasm” for any park plans. While perhaps lacking vision, they had a point. In the post-war years of labor shortages and financial limits, Brookline would be hard-pressed to find the two dozen workers and budgetary space needed to keep 65 acres, a collection of buildings, and multiple gardens in top form. As chairman of the parks commission Marcien Jenckes told the Brookline Citizen in 1949, “If it just sat there, it would deteriorate materially.”

This prediction would prove prescient. Despite the committee recommendation, the full Town Meeting voted 129-64 in June 1949 to officially accept what would be named Larz Anderson Park. But by 1953, vandals and deterioration led the Brookline Citizen to report that “The manor house, stripped of its furnishings, stands empty and forlorn on the summit of the hill, a decaying symbol of the hopes and grandeurs of the past.” Over the next decade, the entire mansion was bulldozed, the Italian garden was turned into a skating rink, and the Japanese garden, Chinese pagoda, and Four Seasons theater all deteriorated. While much was preserved in Larz Anderson Park, much was also lost.

Even into the 1980s, the park was a kind of “mixture of decay and great beauty” as Michael Berger, president of the Brookline Greenspace Alliance, would say. Eventually, the park was included on the National Register of Historic Places and it received a million-dollar grant for immediate repairs and reconstruction. In the 21st century, a new generation of taxpayers and donors has buoyed the park’s condition.

Today, visitors to Larz Anderson could be forgiven for looking at the lavish carriage house, the historic automobile museum, or even the dramatic view of Boston’s skyline and not worry too much about the grandness of Weld’s past. For when it seems like the entire town is out picnicking and kite-flying on a beautiful day, there’s no better place in Brookline.

Above Left: The manor house at Weld which came down in 1955. (Friends of Larz Anderson)

Center: Isabel and Larz Anderson (Boston Magazine)

Above Right: A postcard of the greenhouses at Weld (Friends of Larz Anderson)