Brookline's "Trial of the Century"

In the 1931 trial of 19-year-old Paul Hurley for first degree murder, defense attorney Daniel Gallagher called his client a “product of our age.” Gallagher argued that “Hurley is a victim of the time we live in. The glorification of the criminal in theatres in movies and literature had made its impression upon him. The idea was inbred in him that the gangster was king and lived in luxury and that it was a laudable accomplishment to violate the law and escape detection.” This argument may sound familiar. Popular culture has been blamed again and again for societal violence through the years — from the Church’s condemnation of “Hollywood sin” in the post-war years to the Gangsta Rap controversies of the ‘90s to the condemnation of video games following the Columbine murders. In actual fact, poverty probably had more to do with Paul Hurley adopting a life of crime than anything he saw on the Silver Screen.

In 1930, Paul Hurley was a broke 18-year-old bellhop at the Commonwealth Hotel in Boston. Perpetually short of cash, he picked the lock of a hotel guest bag, pilfered an automatic pistol, and then conspired with former school chum Thomas Healey to rob a Harvard Avenue drugstore. Hurley told Healey that there was “easy money” to be had robbing stores in Brookline.

On the evening of Sunday, August 30, 1930, after talking over their plan with Healey’s roommate Gordon Wilson, the two boys set out, Hurley holstering the pistol. Standing outside the pharmacy, however, they got cold feet and headed back to Healey’s apartment, eventually along St. Mary’s Street. 31-year-old Brookline police officer Joseph O’Brien, patrolling his beat, noticed the friends trying car door handles along their way. Commandeering a passing motorist named Albert Daniels, O’Brien jumped into the passenger seat and asked the driver to pull up alongside Hurley and Healey.

Hours later, on his deathbed at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, O’Brien would tell a fellow officer what happened next. O’Brien said he called out to the boys as he approached them at the corner of Ivy and Carlton Streets. Hopping out of Daniels’s vehicle, the officer began to frisk Healey. Finding no weapon, he then turned to search Hurley. At that point, the stories diverge. In Hurley’s eventual court trial, the prosecution would argue that Hurley drew his gun and fired on the cop unprovoked, shooting him in the mouth and then standing over him and firing another shot into his abdomen. During riveting court testimony, the officer testified that O’Brien told him: “He shot me in the face but the dirty part of it was he came back when I was on the ground and shot me again in the stomach.” As Hurley and Healey fled the scene, O’Brien, propped up on an elbow, apparently got off a shot that went wide, while Hurley fired back and wounded Daniels, the driver of the automobile. As Healey ran, he discarded his overcoat, which just happened to contain a handkerchief belonging to his friend Gordon Wilson. This would become the key clue that would lead police back to the suspects.

But Hurley told a different story of the shooting. In June of 1931, he would testify that when O’Brien turned to frisk him, he told the officer to “throw up his hands.” He claimed Officer O’Brien then drew his gun and shot at Hurley, putting a bullet through his hat and another through his coat. It was only then, Hurley said, that he fired in self-defense. This story would not be believed.

Before any trial could take place, however, the suspects had to be caught, and both were on the run. Manhunts were, of course, much more challenging a century ago. Indeed, criminals on the lam — not needing to worry about cell phone towers, ATM records, or security cameras — had a fighting chance to escape and create a new identity in some faraway place. Police caught up with Healey and arrested him at the city bus terminal in New York, but Hurley was nowhere to be found. Police suspected that he had fled to Maine, hoping to embark on a passenger ship overseas. In fact, he had escaped south, eventually to Baltimore. He was likely home free — if only for his own mouth. Bragging to a co-worker some ten months later that he was “wanted for murder up in Brookline,” local police were soon informed. Based on the tip, detectives arrested Hurley at Baltimore’s Mid-City Hotel, where he grimly told officers, “Sorry, I haven’t got my artillery with me.” Shackled to a detective on a northbound train, he was soon back home to face justice.

That justice would prove to be swift and unwavering. Turning state’s witness, his old buddy Healey told a Norfolk Criminal Court jury that Hurley had fired the shots that killed O’Brien. Healey would not face any jail time, but after just 2 hours and 15 minutes, the jury found Hurley guilty of first-degree murder. The Boston Globe described Hurley’s reaction upon hearing the verdict: “His jaw dropped. He appeared to be close to tears. His hand, resting on the rail before him, fell listlessly back to his side and he stooped as though under a blow.”

The following week, Judge Elias Bishop sentenced Hurley to the death penalty by means of the electric chair. Appealing for clemency to liberal Massachusetts governor Joe Ely, an opponent of the death penalty, attorney Gallagher argued that Officer O’Brien had illegally frisked Hurley without due process and that the crime was not planned with “malice aforethought.”

Nevertheless, Governor Ely denied the appeal and soon Hurley sat in the “death house” at Charlestown State Prison. On September 14, Hurley said his final words to Reverend Ralph W. Farrell — “goodbye father” — and the convict was strapped into the electric chair. A minute after midnight, four shocks of 2000 volt electricity shot through Paul V. Hurley’s body killing him instantly.

Above Left: A photo of Paul Hurley electrocuted by the state in 1931. (Boston Globe Achives)

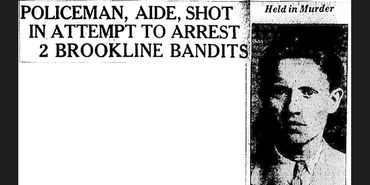

Center: Boston Globe headlines and a photo of Thomas Healey shortly after the O'Brien killing (Boston Globe Archives)

Above Right: The corner of Ivy and Carlton Streets, where the fatal shooting took place.